Exhibition & Interpretive Plan

Baroque Painting: Transformation from the North to the South

Ontario Museum Association and the Art Gallery of Ontario, 2018

1. Introduction

Baroque Painting: Transformation from the North to the South will trace the divergence that occurred within Baroque painting of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as a result of the Protestant reformation, and Counter-Reformation which responded to it. Although the Council of Trent commissioned a dramatic form of history painting depicting biblical scenes to stimulate public faith in the Catholic Church, the Iconoclasm’s secular agenda opened the door for a wealthy merchant society to dictate an art market favoring lower categories of painting imitating protestant society. The northern and southern works, bound together by similar art historical interests, techniques and concepts, will be compared to show how attitudes towards the purpose of art is affected by the cultural context in which it is produced and which influences it’s final form and appearance. Ultimately, the exhibition aims to show how, like people, a work of art is a reflection its environment. When we think of art historical movements, they are often defined by a set of unique characteristics. It is easier to identify and categorize works this way, both for the museum expert and for the casual visitor. By sticking to this model, however, we miss a great opportunity to realize the closeness of art to the human experience. The exhibition demonstrates that similar social, political and geographical conditions do not necessarily produce the same outcomes in character and appearance. Moreover, objects and people from distinct backgrounds can nevertheless have traits in common. The story of Baroque painting comprises a critical moment in the evolution of art and Baroque Painting: Transformation from the North to the South encourages visitors to see their own personal stories reflected back to them through this moment in time.

2. AGO Institutional background

The Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) is an art museum located in the city of Toronto. As one of the largest museums in North America, it holds a collection of over 95,000 works that range from the contemporary to the modern, including European masterworks and works by the Group of Seven, and highlights works produced by established and emerging Indigenous and Canadian artists. A prints and drawings collection and focused collections in Gothic boxwood miniatures and Western and Central African art also span the collection. The AGO’s mission is to “bring people together with art to see, experience and understand the world in new ways.” A recent renovation and redesign of the gallery space in 2008 by renowned Architect Frank Geary transformed the site into an architectural landmark and a popular destination for photographing tourists. The AGO’s mission is to “bring people together with art to see, experience and understand the world in new ways.”

The vision that guides AGO’s public programming and learning is one that views the gallery as a catalyst for lifelong engagement with art and creativity. Through exploration and experimentation, the AGO will become a place where everyone feels comfortable, finds enrichment and connects with issues of our day. The interpretive mission is to foster creativity, learning and dialogue among diverse communities through meaningful experiences with art and ideas. The AGO promotes interpretive strategies that enable visitors to make personal connections and understand why art is relevant to their lives. To think critically about issues that matter, connect with other times, people and places, and have social experiences with one another. In interpretation, language must be inclusive, contemporary and accessible, use a multiplicity of voices, and recognize that learning can be emotional, intellectual, social and physical.

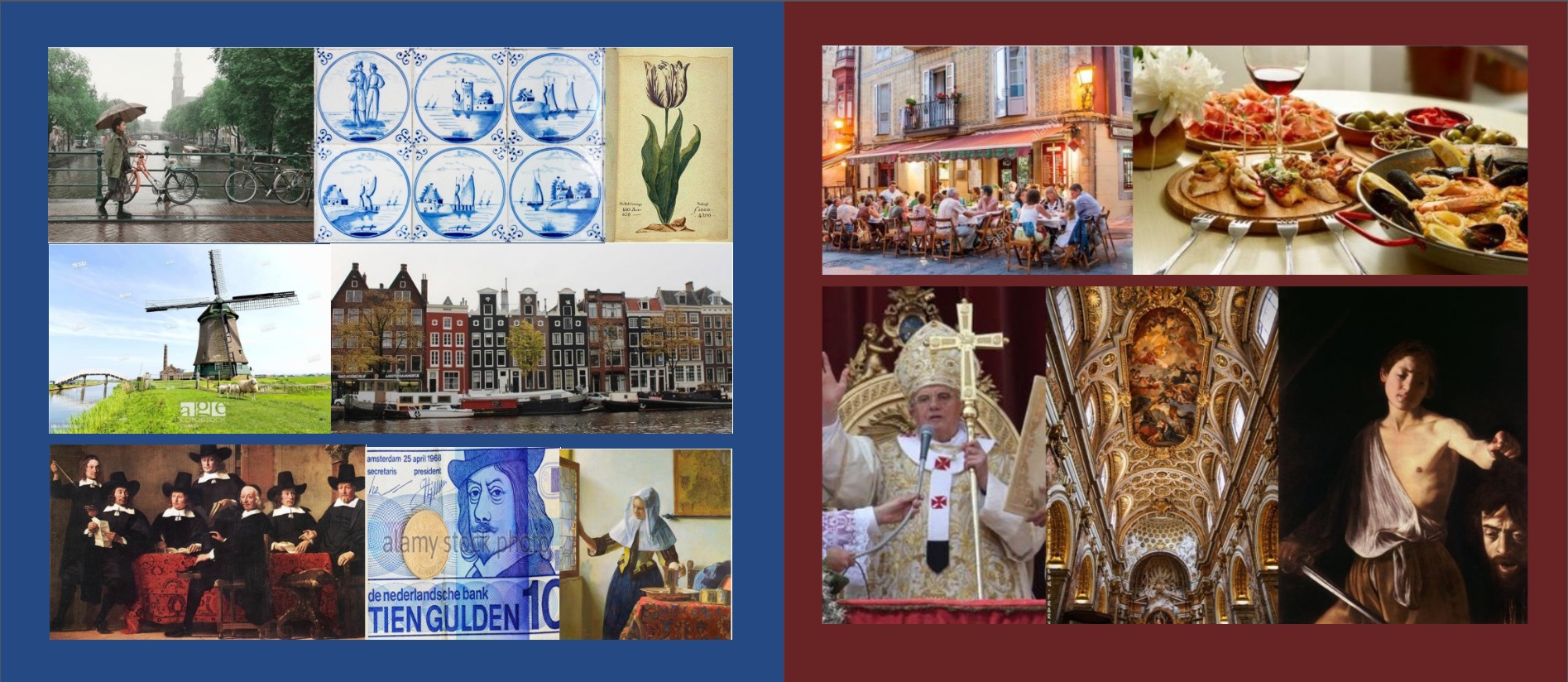

Part I: Southern Gallery

3. Title

The title for the exhibition is Baroque painting: Transformation from the North to the South. The punctuation allows the title to be both evocative of the Baroque movement and factual about the fluid perspective that will be taken. It is engaging, but also to gives the visitor an idea of what the exhibition is about.

4. Big Idea

As it travelled across Europe, Baroque painting transformed to meet the needs and reflect the beliefs of the societies it was produced in. Using this Big Idea as a guide, the exhibit will be devoted to exploring how Baroque painting adapted to its changing environment. Cultural values of the region influenced attitudes towards art and the function it should serve, which altered how artists painted and what they chose to paint. The Big Idea must “move beyond the presentation of information to tell a story.” As Beverly Serrell says, “a Big Idea is a Big Idea because it has fundamental meaningfulness that is important to human nature.” It is for this reason that this Big Idea was formulated, since it highlights the movements’ ability to manipulate itself to better tell the stories of its people.

Inspired by the divergence that occurred within Baroque painting of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the exhibit is about revealing the extent to which the mood and aesthetic of the artform shifted to complement the worldviews of the societies that adopted it. Though the Baroque manifested in a dramatic form of history painting to stimulate faith in the Catholic Church in the southern territory of the counter-reformation, it also showed up in the lower categories of painting in the North to reflect protestant values and Dutch society. In showing how the former occurred, the exhibit will demonstrate Baroque painting’s ability to respond to it’s environment.

Institutional Incentive

The exhibition will place AGO’s impressive seventeenth century Dutch collection in the wider context of the Baroque, and in the context of the Italian and Spanish Baroque pieces of the collection. Most importantly, it will make up for the AGO’s weak holdings of southern Baroque works, by emphasizing the Dutch pieces’ identity as Baroque, even though they do not look like typical examples of the movement.[2] By comparing societies that existed at the same time but held opposing values, the exhibition relates to the mixed ideological and cultural landscape of today, both on a global and localized scale of Toronto. The exhibition also sets up the opportunity for the AGO to realize its important interpretive goal of telling “the view from then” as “stories told from a point of view that considers simultaneous histories and perspectives.”

Visiting Motivation

Museum members, staff, volunteers, patrons of the curator’s circle and others in the immediate community will come to the exhibit because they will be curious about the idea of a Baroque themed exhibition given the AGOs limited number of southern Baroque works. The previous Baroque themed exhibition the institution was part of occurred in 1999 and was only possible with the help of the Capitoline Museum, which supplied masterpieces of the south to tell the story of the Baroque from its traditional vantage point. Others will come to the exhibit because the advertising material will emphasize it’s experiential and transformative nature. Promotional texts will encourage visitors to experience for themselves the “hot-blooded drama of the south” and “meditative mystique of the north.” It will describe an artform that transformed to reflect its society and one that has the power to transport visitors to the same moments in time. Teachers will bring their students because the exhibit connects closely with the Ontario curriculum of grade eleven visual arts courses (AVI3M and AVI30) and related concepts of historical thinking in grade twelve world history courses (CHY4U).

[2] In 1926, painting from Florence was absent altogether [from the collection], as were Italian pictures from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Not until Anthony Blunt want appointed advisor to the AGO in 1948 were “more frequent purchases of Italian art made.” The collecting of baroque art was largely due to Walter Vitzthum from 1963-71, where “a small but limited collection was assembled with limited funds.” This was due to previous collectors’ “puritanical outlook” and “conservative tastes”, where they “could scarcely be expected to welcome into their homes works of art that were highly emotional or sensuous.” Southern baroque works “were liable to charges of immorality and indecency in the city.”

Part II: Northern Gallery

5. Audience

Primary Audiences

The primary audience for which the exhibit is intended are those who Falk and Dierking would call ‘Explorers’. These visitors are “curiosity-driven with a generic interest in the content of the museum [who] expect to find something that will grab their attention and fuel their curiosity and learning.” In Falk and Dierking’s example of an ‘explorer,’ they describe someone who is motivated to visit museums because museums “satisfy very specific leisure-related needs.” Explorers that visit Baroque Painting: Transformation from the North to the South are curious about the different types of Baroque art that emerged during the period and the beliefs and needs of the societies referenced. These explorers expect the different moods evoked by the artworks to grab their attention and fuel their curiosity and learning about Baroque painting, and potentially the artform at large. These visitors would also like a leisure experience and anticipate that they will not have to work too hard to understand the differences between the Baroque pieces because of the artworks’ ability to recreate their environment. The exhibit will address this audience by presenting a southern and northern style of Baroque art from the perspective of the regions which heavily dictated their appearance. The exhibit will emphasize the intended moods with immersive interactives and use a variety of methods when presenting information to cater to multiple learning styles.

Secondary Audiences

The secondary audiences constitute a large portion of visitors. These include: 1) Ontario high school students in grades eleven and twelve due to the strong curriculum links, 2) art museum enthusiasts and professionals whose motivation is for visiting is as ‘professionals’ or ‘hobbyists’ 3) and newcomers to Toronto whose motivations are for visiting as ‘experience seekers.’ Senior grade students have adult-like attention spans and can listen for longer periods of time, think critically and grasp abstract thought. They value independent thought, peer-based discussion and inquiry, and are knowledgeable about current events and real-world issues. They have strong thoughts and opinions and are willing to express them through discussion and debate. These students are interested in art, have had exposure to the elements and principles of design and have been introduced to the connection between art and society. They will be willing to conduct formal analysis within their reach. Art museum enthusiasts and professionals have heard about the Baroque period before; they have seen works of the south and are familiar with its characteristics and major artists. They will be interested in learning about the shifts made by the movement and be quick to assess whether those shifts co-coincide with their previous knowledge and understanding of the period. The last secondary audience is interested in visiting to experience a major tourist destination of the city (the AGO), because it has been advertised in travel brochures they have read. Experience seekers will visit the exhibition on display because it is the latest and greatest of what the institution is up to. They will likely have no previous knowledge or interest in the content.

6. Means of Expression

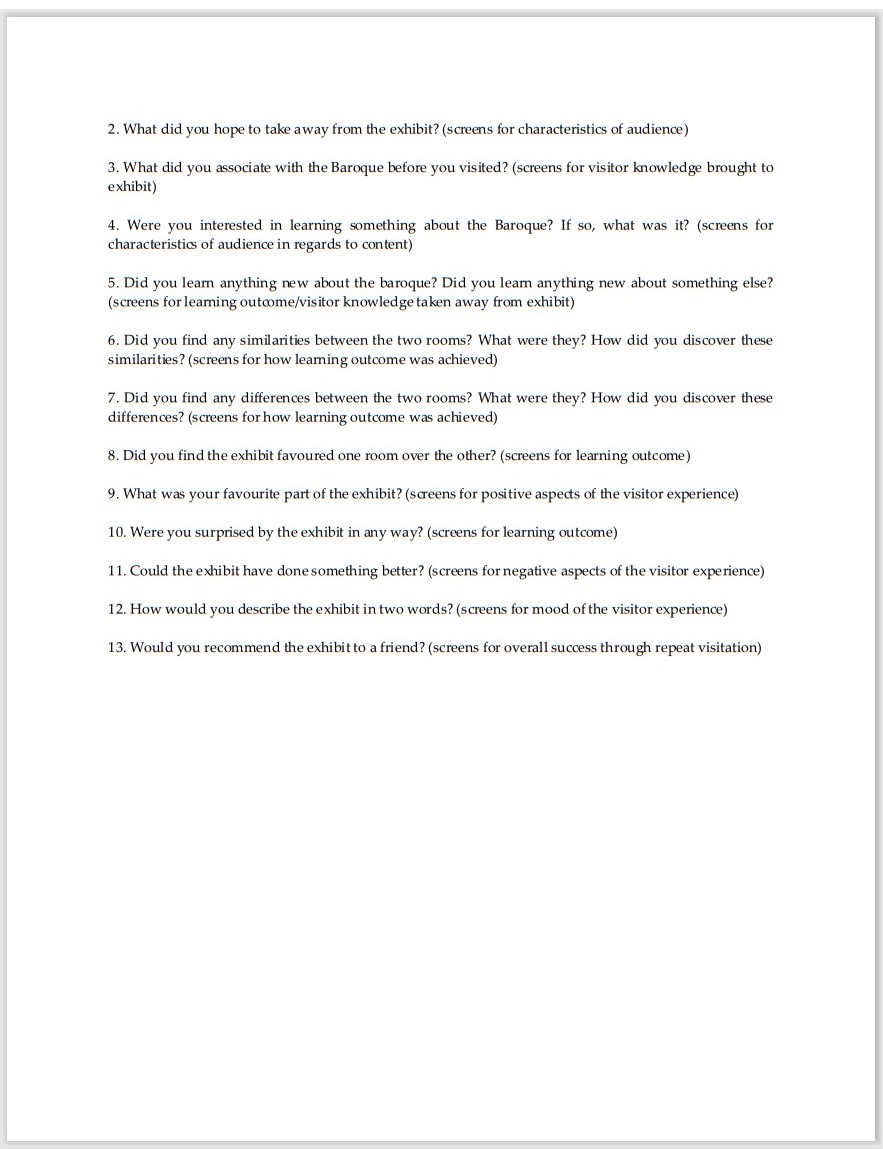

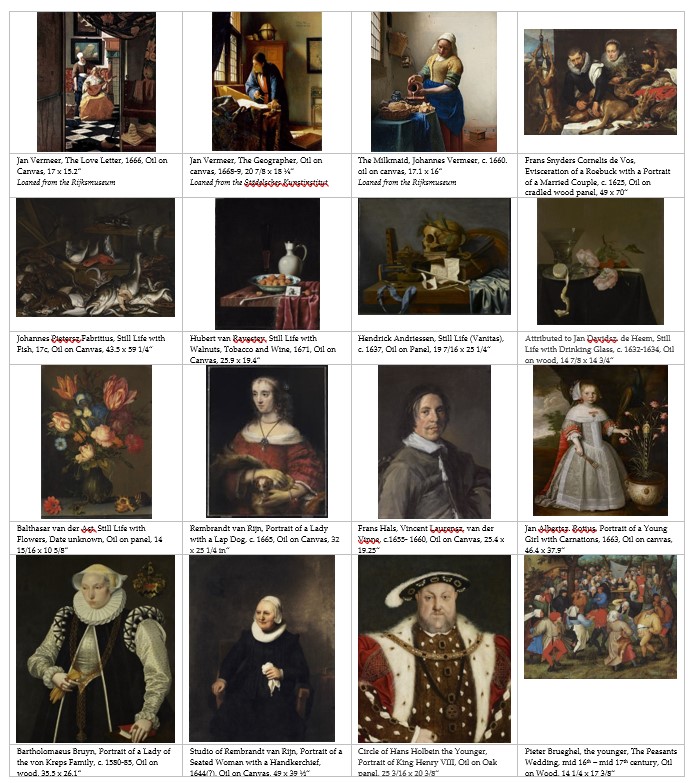

Artifacts

The artifacts used are part of AGO’s permanent collection with loans from international institutions. These loans include pieces by seminal Italian and Spanish Baroque painters Caravaggio and Velasquez that expertly communicate important themes in the first section of the exhibition (the use of chiaroscuro and exploration of violent subject matters).[1] Domestic interiors by Pieter de Hooch and Johannes Vermeer are loaned to make present an important genre of Dutch golden age painting. These scenes describe the attitudes, behaviours and common sights of Netherlandish culture that sets the mood of the second portion of the exhibition. Works by Hendrick Corneliez Van Vliet and Job Adriaensz Berckheyde depict the absence of religious art and the explosion of the art market in Northern territories which will help viewers visualize the context of the second section of the exhibition. The objects supplied by AGO’s permanent collection are Baroque works: mostly paintings, some prints and one sculpture.

Interactive 1: Responsive Map

When asked to describe what constitutes a positive museum learning experience, visitors in a 1986 focus group listed “memorable” as the number one quality. The exhibit will provide many opportunities for interactive experiences, especially effective for explorers who “by and large remember what they saw and did.” In the first section of the exhibit, an interactive map will be used to emphasize the southern Baroque as the home of the Catholic counter-reformation. It will identify where the counter-reformation took place and where the reformation took place (the territories coloured to match the wall colours of each room). If touched, the map will indicate where major Baroque structures live to this day and where major Baroque creatives were active. An image of the Catholics and Protestants “fishing for souls” will provide visual learners with the concept of a conflict between two groups while the map will aid logical viewers. In maintaining with a constructivist theory in approach, introducing context or locations through maps and timelines allows visitors to build on prior knowledge and familiar entry points by understanding through graphic representation (Hein).

Interactive 1: Responsive Map (Above)

Interactive 2: Chiaroscuro Light Room

The impact of Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro was widespread over Europe because of the dramatic effects it produced. To provide viewers with the opportunity to pose, touch, and act, a dark ‘shadow play’ room is included for viewers to better understand chiaroscuro in practice. In this room, viewers can manipulate a light source to illuminate their bodies and faces from various angles, casting their shadows on a wall behind them. A mirror beneath the light source allows participants to view themselves as if they were subjects in Giordano’s Judgement of Solomon (hung prior to the entrance of this interactive.) This interactive is accessible to all visitors but will likely be most interesting to facilitators with children, since children have “uninhibited exploratory behaviour” and “instinctively investigate things with their hands.” Adult facilitators who “seek structure or direction,” could be inspired to participate by observing their children who “charge ahead without [instruction].” Rechargers who are motivated to visit museums for their restorative properties could find in this interactive a moment that achieves “their quest for solitude and awe.” In either case, this interactive gently guides visitors to make discoveries about the dramatic use of light that was so essential to Baroque painting.

Interactive 2: Chiaroscuro Light Room (Above)

Interactive 3: Responsive Still-Life Builder

The next section of the exhibit discusses the growth of the still-life genre. Its growth was caused by artists’ desire to meet the demands of an emerging art market driven by wealthy merchants who valued collecting and recognized individual artist talent. The interactive for this section will explore how artists satisfied this demand and their commissioners. 3D printed objects imbedded in a wall space will provide tactile learners with the opportunity to build their own still-life on a multi-leveled platform. When the object is removed from its cavity, a lit text will reveal the object’s symbolic meaning or societal use. When the object is returned to its place, the light and label will be turned off. This provides viewers the opportunity to build, create and touch while selectively learning about still-life and northern culture. Depending on the type of object removed (vanitas or trade-related), labels will reveal how artists celebrated the accomplishments of their merchant buyers by picturing foreign objects won in trade (porcelains or silks) or by appealing to popular protestant allegories of the fleetingness of life (vanitas, through skulls, pipes, and other ephemeral objects). Artwork labels will discuss Baroques themes of space and naturalism, which still-life artists used render textures and objects realistically. A map depicting Dutch trade routes and goods traded will demonstrate the prevalence of trade in the north and the rich mercantile community. This is a key aspect of the cultural context of the north, and so graphic representation will again be used to provide access to multiple learning styles. As a form of “active, experiential learning in problem-solving, enquiry based and hands on environments, [discovery learning] supports active engagement and fosters curiosity.”

Interactive 3: Responsive Still Life Builder (Above)

Interactive 4: Holographic Interior Room

By capturing the quiet moments of the seventeenth century protestant household, artists like Vermeer and De Hooch were working in the Baroque theme of time to communicate the complex politics of vision occurring in Dutch culture.[2] These artists’ interior scenes of cartographers, housemaids, and courting musicians demonstrated the Baroque interest in light from their inclusion of windows which were central to these compositions as metaphors of the sea-fearing world. To engage musical learners, headphones playing Baroque music will be included beside paintings of lute players to make the artifact more memorable through multi-sensory experience. A reconstruction of a window-side interior scene with an accompanying snap-chat filter will be included to encourage social learners to have their pictures taken as cartographers or housemaids. Artists painting interior scenes of this type would often include artwork in their compositions that would serve as indicators of what their subjects were thinking about (seascapes for married women concerned about the safety of their husbands abroad, and maps of the world for practicing cartographers). When the filter is activated, visitors will be cloaked in the same garb as the figure they select, and a matching composition will fill the empty picture frame behind them. The window of the reconstructed interior scene and its open-face places visitors in a position of seeing and being seen, recreating the experience of what it was like to exist in Dutch culture at the time. Milk jugs and globes will be placed on the table for visitors to pose with, supporting the identity of the subject they choose to imitate and the ‘snap-shot’ quality of time captured in Dutch interior scenes. The elevated platform of the interior scene is accessible by ramp and inclusive of visitors using wheelchairs by not obstructing them from using the table. Interactives such as these move wall texts into the gallery space and stimulate curiosity within visitors to learn more about the content.

Interactive 4: Holographic Interior Room (Above)

Interactive 5: Textured Paint Swatches

In section two of this portion of the exhibit, the Baroque theme passions of the soul is applied by artists to capture the character of their sitters. Object texts of this section will uncover the identities of sitters as merchants, aristocrats, or marriage partners. In this section, the words “Avant-Garde or Typical?” will be written above the Isaac Massa and Michel Le Blon portraits hung together. A textured oil swatch beside the Hals portrait and a smooth oil swatch accompanying Van Dyke’s portrait will allow physical learners feel part of the answer to the question. The Instagram hashtag prompt, “Do these sitters remind you of anyone you know? Take a photo of your favourite detail and tag them!” will encourage viewers to see their friends and family in Le Blon’s composed nature or Massa’s charismatic character and look closer to find the technical accomplishments in both styles. Artwork labels will address differences in brushstroke, which will provide an answer to the question listed above the portraits.

Interactive 5: Textured Paint Swatches (Above)

Interactive 6: Tools for Debate & Discussion

In addition to physical interactives, there will be interactives included to stimulate discussion and relate works to today.

The last section of the southern gallery explores Baroque artists’ obsession with the concept of time and use of morbid narratives to portray extreme states of feeling through their figures’ facial expression and body language. To enforce the theatrical effects of depicting violent moments in time, a velvet stage curtain will be used to frame Ruben’s Massacre of the Innocents. The same seating that one might find in a cinema or opera house will be provided in front of the painting, to give viewers the sense that they have walked into a play at its most climactic moment.

To relate past works with present perspectives, a voting board is included by Caravaggio’s piece to stimulate debate and relate his story to issues of today. The first screen displayed on the digital interactive will read; “The violence depicted in this image was not unlike the violence of Caravaggio’s transgressions. Because of his scanty reputation, some scholars believe his work should not be shown. Should we consider the character of the artist in criticizing their work?” Visitors will have the option to vote by choosing from the answers “Always” “Never” or “It depends.” Visitors will also have the option to choose a second path, that reads “I would like to know more about Caravaggio’s past, and how it relates to issues of today.” This path will be symbolized by the safe space triangle and warn visitors that some content may be triggering if they choose to view it. Visitors will then be rerouted to the explicit version of the question, which describes Caravaggio’s transgressions in detail. The text will read “Some scholars believe the woman pictured slaying Holofernes was inspired by a brothel worker whom Caravaggio had relations with. After getting into an argument with her employer after a tennis match, Caravaggio murdered him in the streets of Naples and was later forced to flee the city. Because of his scanty reputation, some scholars believe his work should not be shown. When should we consider the character of the artist in criticizing his work? For example, are the actors involved in the #MeToo movement still deserving of roles?” Visitors will have the option to vote by choosing either “Yes,” “No” or “Maybe.” After selecting their answer, they will be shown the results of the poll and how others have voted.

To contextualize Northern artworks for visitors, a timeline will be included at the beginning of the section that that describes the events that led to the protestant reformation and iconoclasm that followed. The destruction of culture is an ongoing issue that will be demonstrated by the example of the destruction of art occurring in the middle east by militant groups. After this, a wall text will ask visitors the question, “How can we use resources of today to preserve culture for the future?” Visitors will be encouraged to discuss their answers with each other or respond on social media platforms with the gallery’s provided Facebook and Twitter tags. Prompts such as these are designed for parents and visitors in their late twenties, who comprise 26% of visitors to the AGO and 44% of Wednesday night visitors to the institution.

[1] The AGO has received Caravaggio and Velasquez paintings on loan by prominent Italian cultural institutions (the Musei Capitolini) in 1999.

[2] These included families leaving their doors open to display efficient domestic work by both husbands and wives (the work ethic of which stimulated the Dutch economy) and their family coat of arms which indicated their wealth and status

7. Character of the Visitor Experience

Visual Inspiration

Visiting Expereince

From an experiential point of view, the goal of the exhibit is to excite and refresh. Visitors should be grabbed by the exuberant works of the southern room and surprised by the different quality of works in the northern room. Visitors should also experience a dialogue between the two works that shows their formal similarities to be as prominent as their cultural differences. The tone will present both cases with equal enthusiasm, leaving it up to the viewer to decide which interpretation of the baroque they prefer. Remedial interviews will be conducted by floating gallery guides to determine if the exhibit feels to visitors as it is intended to by exhibit designers. The content of the exhibition is Baroque works from the highest to the lowest categories of painting, however, they are structured by region and mood rather than chronologically. For the New Walk Museum in Leicester, using a thematic approach “encourage[s] thought and the making of connections, both between elements of the displays and in terms of visitors relating display content to their own experiences.” In the context of this exhibit, the thematic structure will encourage visitors to make connections between the two groups of works and relate them to their own lives. The New Walk Museum’s design brief goes on to say that a thematic approach allows them to “pace the displays by selecting different interpretive priorities for each theme.”

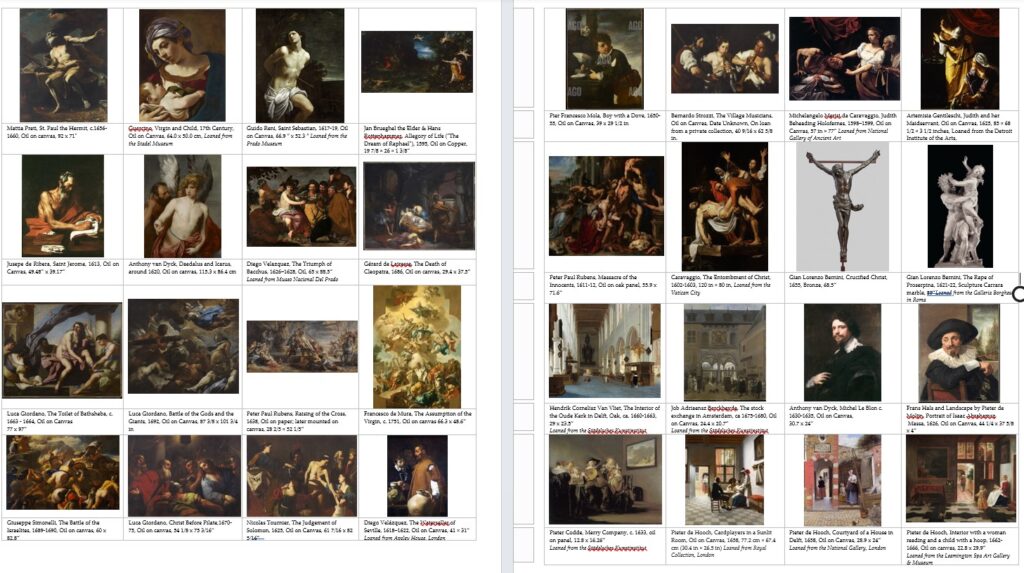

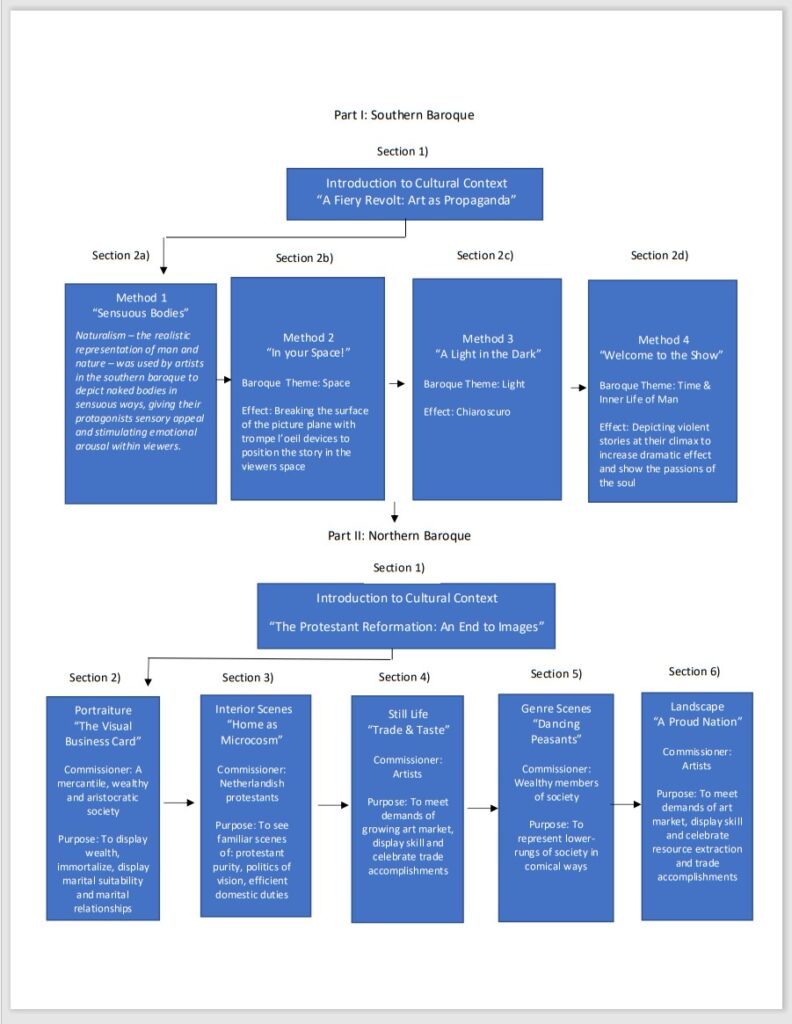

Exhibition Structure

A flow chart is included above to illustrate the thematic flow of each gallery. Within each gallery section, sub-themes are included that will help visitors understand the main interpretive priorities for each region. For example, the sub-themes in Part I will help visitors understand the five major themes of the baroque – naturalism, space, light, time, the inner life of man – and their dramatic application. While these themes are formal in nature, the themes in Part II are contextual. This is because another goal of the exhibition is to have a conversation about art as a reflection of society. Because of this, it is important to show the characteristics of northern society that incited a Dutch-style application of Baroque themes to occur. Structuring Part II by the lower genres of painting will help visitors understand the cultural motivations that supplied the conditions for a Northern style of baroque painting to take place.

Object labels for works in Part II will include formal analysis that describes the softer application of Baroque themes that were introduced in (and provided the structure for) Part I. Similarly, object labels for pieces in Part I will give a brief description of the painting’s mythological or biblical story and identify where a dramatic application of the theme can be seen in the composition. As Summers said of the exhibit design process, it “is a creative process that can have a didactic outcome, but a purely didactic process will not necessarily produce a creative outcome.” An exhibition structured purely around formal analysis would not produce a creative output; an important guiding principle for making good exhibits. By placing formal analysis within object labels (the second tier of interpretive text after wall texts) it will allow visitors many opportunities to investigate, make observations and test themselves to see if they are right. The primary aim of the exhibition is for visitors to experience the different moods evoked by each region – and, by extension, the diversity of the Baroque style – and “if some visitors learn and others are (only) delighted but do not meet the stated learning objectives, we have still done a good day’s work.”

Educational Programs

During programs offered in conjunction with the exhibit, students will be encouraged to think about the diversity of Baroque painting and detect emotion in it by observing, reacting, touching, feeling, listening, imagining, posing, creating, sharing and discussing. Similarly, audiences visiting the exhibit will look closely at paintings, manipulate sources of light, explore map layers, feel dried paint, build still lifes, share thoughts, discuss reactions, listen to music, and pose as subjects. To discover and construct their own meaning, students and audiences will be encouraged to make connections between then and now; between the work of art and their own experiences. To develop strong toolsets for learning into the future, students will be encouraged to think from multiple perspectives, make informed choices, work individually and collaborate with peers. Programs will include “On the Dot” art chats, floating Gallery Guide conversations, and booked groups including curriculum-based school-age field trips. Considering the number of artifacts being exhibited, the expectation for an average length of stay is typically one hour depending on the characteristics of the visitor group. For younger school groups, an average length of stay could be forty-five minutes to one hour whereas older students and adults have longer attention spans and could spend up to one hour and a half in the exhibit. According to Black, “museums need to do much more observing, tracking, recording and interviewing in “real time.” Taking this into consideration, an observational study will be carried out by special exhibition staff once the exhibit is open to ensure these figures are accurate. Based on results, programs will be tailored to adjust the amount of content discussed.

8. Learning Outcomes

The tendency is to overestimate the knowledge and understanding visitors bring to exhibitions, as shown by a study conducted by the Cleveland Museum of Art. In this study, the museum found that “even frequent visitors are not as familiar with the Museum, its art works and art history as we had assumed them to be.” If Explorers (the primary audience) consider visiting museums to be a leisure activity, it can be assumed that they have had enough experiences in museums to draw a conclusion about how they feel about the museum visit experience. If they are frequent visitors, they may have had exposure to different artistic movements and collections. They may have heard or recall the term Baroque, and maybe even remember viewing a Baroque gallery. Infrequent explorers could have as little as no previous exposure to the Baroque, let alone an understanding of the artistic periods and the art historical cannon. Either way, both types of explorers are curious to increase their familiarity and understanding of the subject matter. Senior grade students can also be expected to have little or no previous knowledge of the Baroque, but fine arts students may be more apt to understand the content of the exhibit due to their familiarity with the elements and principles of design that will guide them when making comparisons. Museum enthusiasts and professionals will have some to a high degree of knowledge about the subject matter, while experience seekers can be expected to have no previous knowledge of the subject matter.

Front-End Evaluation & Pre-Visit Baseline

Through front-end evaluation, a pre-visit baseline will be established to ensure the accuracy of these expectations. Interviews and questionnaires that ask open-ended questions will be used to collect qualitive data about visitors’ knowledge and interests, such as: What do you associate with the Baroque movement? What are you interested in learning about the Baroque period? What do you expect to take away from the exhibit? These questions cast a large net that does not pigeon-hole participants in the same way a direct question about their knowledge regarding the subject matter would. In their responses, it is hoped that visitors will associate exuberance, grand architectures and elaborate churches with the baroque period and hope to learn more about the movement’s application to painting. If they show less knowledge than this, the interactive maps and wall texts that introduce the cultural content will get these visitors up-to-speed. All types of visitors should leave with an understanding of the diversity of the baroque painting, from content depicted, to cultural motivations, to mood and style. Based on their pre-visit opinions, visitors may find their own views of the Baroque challenged or broadened. By providing insight into the fluidity of the Baroque movement, it is hoped that visitors will understand the strong relationship between art and society. This includes society’s ability to determine the purpose art should serve, which in turn altered how artists painted and what they chose to paint. It is also hoped that visitors will understand artworks’ importance in promoting and instilling cultural identity, along with their ability to be shared across – and transcend – cultural boarders. If visitors walk away with the notion that paintings from both regions were motivated by the same desire to connect in a personal way with their viewers, that is an added benefit.

9. Text

Text for an introduction panel

As it travelled across Europe, Baroque painting transformed to meet the needs and reflect the beliefs of the societies it was produced in. The Baroque movement penetrated dance, music, architecture and sculpture with its grandeur, exuberance and drama. The Palace of Versailles and the Piano are two Baroque inventions that still captivate audiences today.

The Baroque began in the heart of the Italian South in Rome, where it was hard-set on meeting an agenda of the Catholic church. To slow the developments being made by the Protestant reformation – a new branch of Christianity gaining followers in the North – the counter-reformists held a meeting where they decided on their weapon of choice; painting.The Catholics adopted a propagandistic art to extend and stimulate public faith in their Church. Their art was defined by a desire to deliver the divine through emotional empathy. It was hoped that by creating dramatic depictions of religious figures and mythological stories, it would elicit an emotional response within viewers that would cause them to connect personally with the Church and extend their devotion.

Text for a secondary panel

Naturalism – the realistic representation of man and nature – was used by artists of the southern baroque to replace impossible gods with real people. They were real because they were convincing; their faces were subject to the same aging and imperfections detectable in the viewers who saw them. And, if you didn’t believe they were real people, the artists would remove their clothes to prove it to you. Disrobing figures imbued narratives with sexuality and seduction, further stimulating sensory appeal and emotional arousal within viewers.

Text for three artifact labels with an image of each artifact

Artifact label 1 – Mattia Preti, St. Paul the Hermit, c.1656-1660, Oil on canvas, 92” x 71″

Who is this man, and why is this bird out to get him? In the Bible, St.Paul fled to the desert to live a life of prayer, abstinence and fasting. Saints were not just good people, they were said to have God within them that would manifest itself in miracles like this raven bringing St.Paul his daily ration of bread. In his surprised expression, twisting pose, spot-lit, vascular body and the climactic moment shown, we see everything that made the Baroque Baroque.

Artifact label 2 – Peter Paul Rubens, Massacre of the Innocents, 1611-12, Oil on oak panel, 55.9” x 71.6”

Imagine you have just walked into a play, what is going to happen next? In the Gospel of Matthew from the New Testament, King Herold ordered the execution of all male infants in Bethlehem that were two years old. By choosing to paint this exact moment of the massacre, Rubens had the opportunity to move us with the anguished expressions and defensive postures of these lamenting mothers.

Artifact label 3 – Frans Snyders Cornelis de Vos, Evisceration of a Roebuck with a Portrait of a Married Couple, c. 1625, Oil on cradled wood panel, 49” x 70”

It wasn’t a custom at the time to put on your best linens and gut a deer in the living room surrounded by food…There would not have been a second date after this! This portrait was a construction commissioned in order to showcase the couple’s wealth; that they had the means and land on which to hunt. Naturalism is used to emphasize their goods: deer seems to smile at you, and delicate fingers point to fresh grapes.

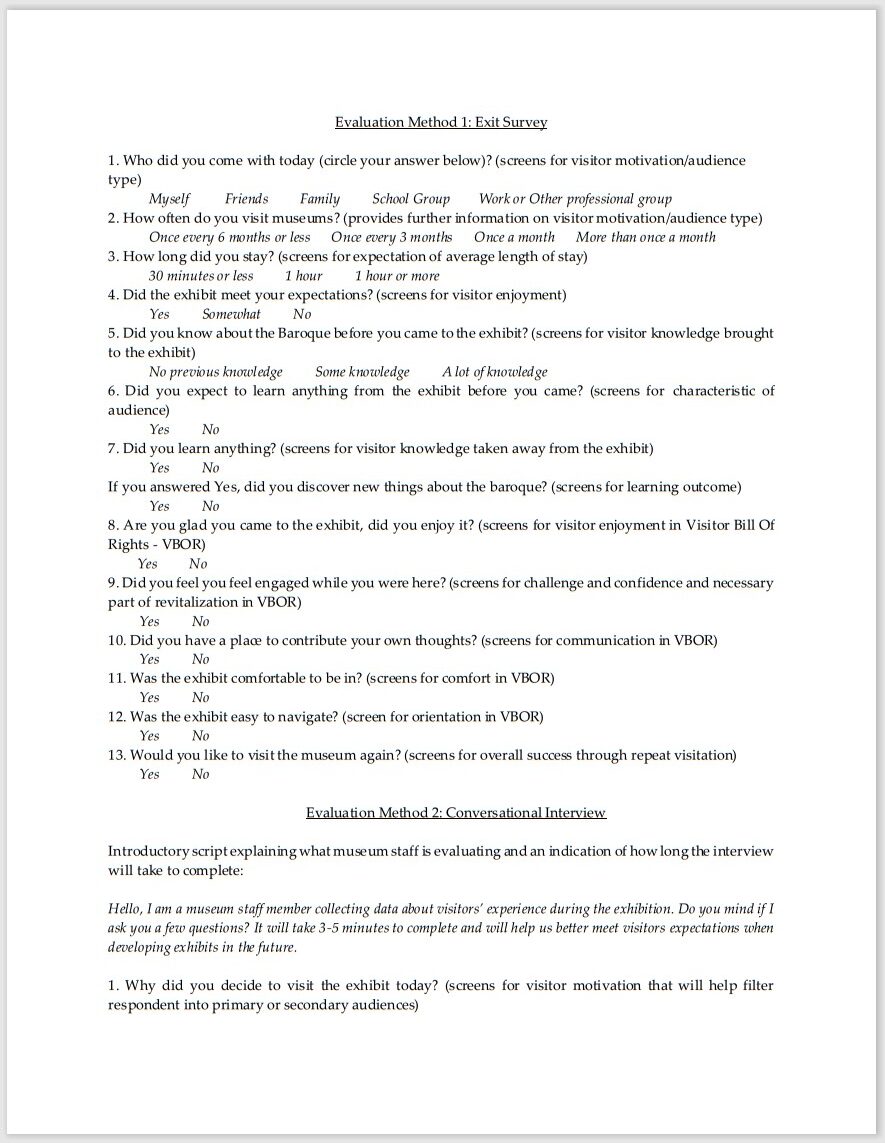

10. Evaluation Plan

In the last month of the exhibit, a summative evaluation will be carried out. The goal of the evaluation project is to measure the character of the visitor experience and intended learning outcomes. According to Summers, the personal experience of visitors (which doesn’t necessarily have to do with the content of the exhibit) is crucial in determining whether the exhibit experience is a good one or not. For exhibition designers, meeting visitors’ basic needs must come first before we can expect them to engage with content and interactives. These fundamental elements, what Summers calls “The Visitors’ Bill of Rights” must be adhered to for a successful exhibition to take place. For this reason, evaluation methods will ask questions that address this essential aspect of the visitor experience, to figure out if visitors’ basic needs were met. Evaluation methodologies will probe deeper into the character of the visitor experience, to get answers to questions like What was the mood of the exhibit? and How long did visitors stay? They will also seek to answer questions about expected learning outcomes, such as What did visitors bring to and take away from the exhibit? Did visitors understand the Big Idea, which yields the learning outcome? If so, how did we achieve this? Methodologies will also ask questions about the audience, to provide more context for the data collected, such as Who visited the most? Did the target audience visit the most? Where they interested in the same things we thought they would be interested in? Did they have the same knowledge and understanding we expected them to have?

The evaluation will compare the experiences of different groups of visitors, exploring how different groups of visitors experienced the same exhibit. The data will be collected by three methods. The first is a survey that visitors will be encouraged to complete on their way out using a touch device. This survey will collect quantitative data using questions that require quick, yes or no responses, to limit the duration of the evaluation. Structured conversational interviews will ask-open ended questions to gather detailed, qualitative data about what visitors learned and experienced during the exhibit. These methodologies screen for most of the “Visitors Bill of Rights,” but not all. An observational study will be carried out to determine Belonging, Socializing, Respect, Choice and Control and Challenge and Confidence. During observation, observers will ask themselves; Are the staff making visitors feel welcome? Are visitors socializing? Are visitors shying away from object labels and parts of the exhibit, because they do not feel respected for their own level of knowledge and interest? Are visitors touching and getting close to whatever they can? Do visitors seem anxious or bored?

To carryout the conversational interviews, the museum will need a maximum of 56 volunteers (assuming there are no repeat volunteers, and each shift lasts 3.5 hours, and the gallery is open 6 days a week and 7 hours a day). One member of the educational staff will have to train each group of volunteers the week before their shift, amounting to four one-hour training sessions. A staff member will also have to create the iPad survey, with a user-friendly interface. Docents and gallery guides who will be used carryout the observational study will require no training, since they will already be familiar with gauging visitors’ attention and behaviour on the gallery floor.

Interns and summer students will gather the data and the interpretive planner and exhibition designer will write and present the report to curatorial staff, members of their own departments, the education department and board members. Docents and volunteers will be welcome to attend the presentation. Assuming the exhibition will bring in a total of 70,000 visitors during its six-month span (half of the museum’s last blockbuster target audience figure), during the evaluation period of one month, 11,592 visitors will come to the exhibition. If only five conversational interviews and five visitor surveys are completed per hour, 14% of the total target audience will be evaluated by the end of the project. If up to ten conversational interviews and ten visitor surveys are gathered per hour (with 69 visitors per hour), up to 28% of the total target audience could be evaluated to produce meaningful results.